Like many young prostitutes in Berlin, Azura had a dayjob. Due to reasons too numerous to go into here (in which time is limited), the fees a prostitute could typically expect in exchange for the usual requests had withered, over the decades, to very stern figures. A young prostitute of some refinement today working in the strongest economy in Europe can expect the kind of money a milk-fed whore from a small country would have been disappointed to earn in the 1970s.

Such whores were now limping up and down the Kurfürstenstrasse, the scraped habitat of tattooed white junkies and abstemious African exchange students, offering the total inventory of their butchershops for a pittance. Like the feather-sprung, peg-legged pigeons these damp women shared the curb with, time appeared to be dismantling them with extraordinary impatience. There was a rumor that some of the oldest or most naïve had been selling off toes and now fingers to pay for bigger, sturdier implants.

Four days a week, Azura worked as an intern for a fledgling film production company called Auslandish Films, on Rosenthaler Strasse, in the Mitte neighborhood. Her wage as an intern was minuscule, barely drink money, but she believed she was getting her foot in the door of the film business. Azura resembled a film star herself, in a 20th century way, with a defiant posture her customers at the brothel interpreted as a welcome challenge.

Azura’s boss at Auslandish Films was a soft-spoken Afro-American expat with a dent in his chin named Mr. Jeffries, fluent in German, with an arrogant wife and three cookie-colored children, the oldest, a boy, not much younger than Azura. The boy was trouble but he rarely showed up at the office. When he did, he made such an exaggerated show of ignoring Azura that it was the same, in Azura’s opinion, as staring at her. His hair was in soft slow shoulder-length loops the color of broken butter, floating in the invisible currents of resentment he seemed to move through. His own lazy ocean of Balthazar Jeffries.

Saturdays were the only days on which Azura worked both jobs, stopping in at Auslandish in the morning (opening up with her own key and code to the alarm) to deal with overnight post and important answering machine messages and then riding her scooter across town to the neighborhood of Charlottenburg, on Blissestrasse, where Lady Luck, her brothel, took up the second and third floors of a grand old building that had quite nimbly dodged aerial bombs during the war. The rest of the block had been stomped to rubble when Azura’s grandmother was just a pretty girl on certain lists and the graves of these buildings, after a strange dormancy, had all sprouted modern flatblocks.

On the Saturday morning in question Azura inadvertently intercepted a private message from Balthazar Jeffries to her boss Mr. Jeffries on the answering machine. It was the last message on the tape and was so long that the tape ran out in the middle of an already almost-incomprehensible sentence. Azura played the message back three times, hugging herself in the cozy morning gloom of the empty office. Azura recognized immediately Balthazar’s voice.

There were scant gaps between the words in Balthazar’s diatribe against his dark-skinned father and Azura knew from experience which drug was involved. Balthazar Jeffries insinuated more than once that the answering machine message could probably be taken as a suicide note. Tell Mom and Becky and Gladys and so on. Azura had to come to a decision as to whether or not to delete the message before re-activating the security system and locking up shop again and driving across town to the brothel. If the message was merely the inhuman animus of a drug in full flight’s lava-like oration, Balthazar would be profoundly relieved to discover later that his poor father had never received it. Perhaps Azura might somehow even indicate to Balthazar that it was she who had taken care of the matter. Maybe then might Balthazar humanize Azura with the simple courtesy of eye contact. Or?

Azura dwelt on her decision, and the implications of her decision, the rest of her rainy afternoon in the brothel.

The truth is that the most lucrative services aren’t about sex at all. Azura’s colleague Lilly, for example, had consented to an incision (local anesthetic) about four inches long, in her abdomen, not far from the left kidney, which the medical student who considered doing this a refined pleasure then carefully sutured, returning a week later to undo the threads (local anesthetic again) and probe gingerly, with a sterilized implement, the slackly-smiling wound. For this Lilly received two payments, the first much larger. And Azura herself had once complied with a request to make dirt discreetly into a chasteningly-expensive triple-gusseted flapover briefcase of real alligator. The perfect little model of a Milk Dud. One month’s gas, water, phone and electricity bills all neatly dispatched with a grunt.

Such things happened in the neutrally-decorated chambers of Lady Luck, a converted gerontological clinic, where Azura paid rent for a smaller room overlooking the courtyard. In the courtyard twisted a chestnut tree whose fecund arms reached her window, nagging her about the past, wagging an appointed finger when Azura bent over the little bed or mounted it on all fours with her face to the window.

Every weekend during her happy childhood, Azura had slept at her grandmother’s. Two nights she sat up in her little bed crying. Her Nana was a woman from a small country of ritual and habit who only took her hair down when it was bedtime, before her prayers and after her hot milk and a nice fashion magazine. She climbed the stairs to the room where the ceiling slanted down towards the window by Azura’s small bed and asked her Azura, with the militant compassion of a saint, why Azura was crying.

–Weil der Neandertaler nicht in den Himmel kommen kann, the child answered, with a gulp after every word. Because the cavemen can’t get into heaven.

-Say again?

-The cavemen, she repeated, miserable. You said they were born before Christ Nana so how can they can ever be angels and go to Heaven?

-No, no, cooed Nana, softened by the sudden truth, stroking Azura’s forehead with a trembling hand and confronting her own blunder in this fine-cut grief. Bible stories were always distressing for younger children, who hadn’t yet learned to bend or strangle logic. In her diaphanous nightgown and shocking dark tumult of hair Nana resembled an excluded angel herself, cooing how the Christian God would never be so unfair like that, Azura. The good cavemen, they will go to Heaven. Don’t worry. Go to sleep.

-Even if they didn’t know it was a sin to kill, Nana?

-Even so, said Azura’s grandmother, with somewhat less certainty in her voice but the persistent desire that the child should go on peacefully to her dreams. She who was given to fevers and days on end of pretty speechlessness. Mother a sinking stone and father an old suit in some faraway closet.

The next night Nana was drinking her milk and re-reading the magazine (the hypnotic offense of raw youth in proud clothing; the communists would never have allowed it) when again she heard the prayer-like murmur of abject misery in the attic. Up the stairs she climbed, lifting the hem of her nightgown with one hand and clutching the candle holder with the other.

-The cavemen, Azura gulped.

-They’re in Heaven. Don’t you remember? The cavemen are in Heaven near God.

-Yes, answered Azura, but how can cavemen be happy in Heaven? They can’t talk with the others. They aren’t wearing good clothing! The others will treat them like animals Nana! How will the cavemen be happy?

Nana had to admit that it was difficult to imagine cavemen with angel wings flying around a standard Heaven, brandishing their clubs.

-The Christian God is wise, she responded, after thinking a while with her eyebrows so high they were straining. About such a problem he’s already thought, before creation, even. He has given the cavemen their own Heaven and there they are happy.

-There’s a caveman Heaven?

-Yes.

-And no one else can go there?

-No one else can go there, confirmed Nana. To point and laugh, she added, smoothing Azura’s astonishing hair. No one.

Rainy days brought out the worst kind of customer, for it was usually the type, on rainy days, who would otherwise have been occupied, enjoying the weather in a convertible, with a beautiful amateur, had the sun been willing. She preferred the business of the damp white cast-offs who skulked in out of a glorious day, mocked by the splendors of existence. They were very quick and humbly predictable and rarely had the money to propose something frightening. But of course such visits only covered a few hours of overhead.

On rainy days, as Azura’s colleague Lilly put it, the snakes use the staircase. Worst of all were middle-aged men with perfect bodies who mentioned the price they were willing to pay, up front, before describing the service they intended to pay for. The good news/bad news technique of the novice oncologist or seasoned sadist.

Azura was curled on the blanketless bed, gazing through the rain-melted window at a sky like cold dishwater and dishwater’s buried shapes, recovering from her last visit, toying with the idea of opening the window to let the bad feelings out. It was suppertime and she was daydreaming about Balthazar Jeffries. She daydreamed a knock on the door; she daydreamed putting on a bathrobe and telling whoever it was to wait.

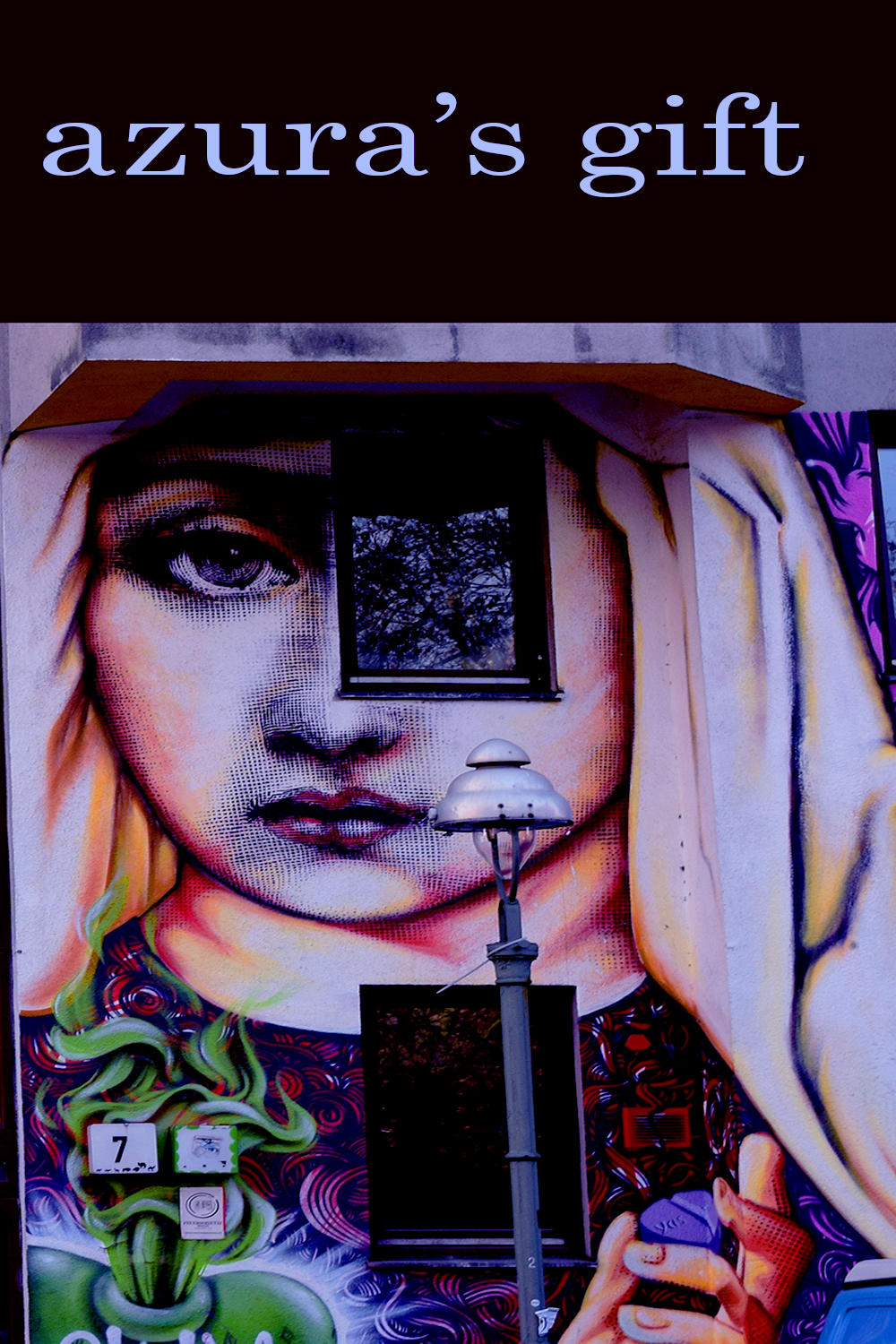

She daydreamed that she’d cross the room in three strides and sit at the vanity, the light from the illuminated mirror the only light in the rain-darkened room, and deftly, very quickly, reconstruct the impenetrable mask of her makeup. Once, a customer had pressed her prone to the bed with his knee between her shoulder blades with such force while he pulled himself to completion that a blurred portrait of her open-mouthed face, like a shroud of Turin, remained on the pillowcase. Or, yes, like that painting on all the t-shirts and postcards.

She’d answer the door and in a horrible miracle and a gift there would stand Balthazar Jeffries, angered by rain and coughing up mud from the riverbed.